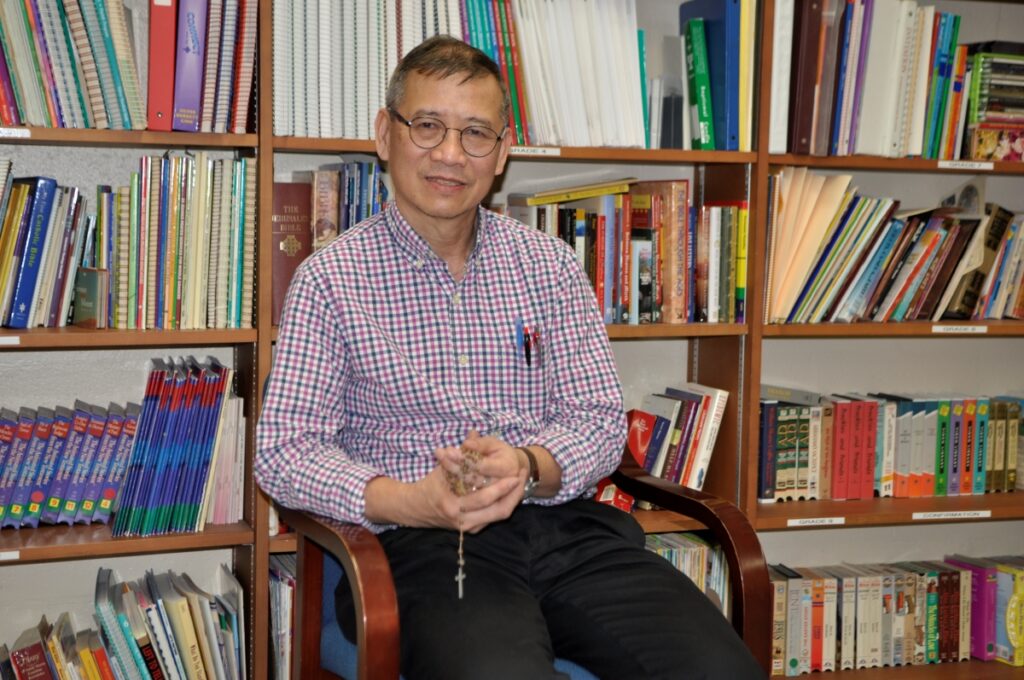

Toan Nguyen holds the rosary he carried in 1980 during his escape from Vietnam. Photo by Shelley Wolf

By Shelley Wolf

WEST HARTFORD – It was 1980 – five years after the Fall of Saigon – when Toan Nguyen (pronounced Twon Nwuyen) passed by his “grand aunt’s” house in Saigon. He had been drafted by the Vietnam army to fight in an invasion of Cambodia and would be leaving for boot camp soon.

As he stopped in to say goodbye, his great aunt, who he called Ba Muc Dang, gave him a gift – a brown plastic rosary – which he now refers to as a “precious keep sake.” He recalls her saying, “I do not have anything else but this humble rosary. Pray with it for your protection and graces. … I will also pray for you, too.”

Nguyen carried that rosary with its crucifix – a symbol of faith and victory over death – to war, which was the beginning of his harrowing escape from Communist Vietnam to freedom in the United States. Remembering the number of times on the odyssey that he turned to that rosary to calm his fears, Nguyen now says, “I feel the faith sustained me through the tough times.”

As October, the month of the Most Holy Rosary, begins, Nguyen treasures that very special rosary. He believes Mary’s intercession helped him to manage his fears and make it to freedom. In his estimation, his safe journey was nothing short of a miracle. Today, he appreciates the life he is now living with his family in peace and security here in the United States.

Nguyen is currently a parishioner at St. Andrew Dũng-Lạc Parish, a Vietnamese Catholic community that worships at St. Mark Church in West Hartford, part of the larger St. Gianna Molla Beretta Parish. This year, he and his fellow parishioners observed the 45th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon, which occurred on April 30, 1975.

Back in 1975, when Nguyen was 17, South Vietnam fell to the Communists. “Why?” Nguyen says he asked himself at the time. “We had the strongest army in the world helping us, and we were defeated.” Everyone was paralyzed, he says, waiting to see what would happen next.

Under Communism, people quickly lost their freedoms and human rights, including religious liberty. Nguyen was living in a seminary back then, studying for the priesthood but the seminaries were closed. The jobless rate rose to 80 percent, food was rationed, and those caught smuggling extra food were sent to labor camps, he says. His uncles and cousins, who had fought for South Vietnam, were sent to labor camps, too. Nguyen worked as a tricycle delivery person to help support his widowed father and four younger brothers, but they still struggled for enough to eat.

Defiant at 17, Nguyen joined an anti-Communist underground organization but got caught, was imprisoned for three months, then released. All churches were under observation, he says, and he was coerced into going against his faith. “They wanted me to spy on the priest at my parish,” he recalls. “I had to write a report on what the homily of the week was.”

“Everybody wanted to get out,” he stresses. Corruption reigned as people took money from those desperate enough to escape in boats. “This is how the ‘boat people’ started.” Half perished at sea, while those willing to flee on foot through Cambodia to Thailand became known as the “land people.”

Nguyen felt trapped – until he got drafted into the Vietnamese army in 1980 as part of an invasion of Cambodia. “If I was sent to Cambodia, I might escape. That was my plan,” he recalls. He thought, “If this is God’s will and my chance to escape, I’ll take it. If I die in the jungle, I’ll take the risk.”

A close-up of the rosary that Toan Nguyen received from his aunt and later repaired with a spoon. Photo courtesy of Toan Nguyen

His next door neighbor, Noi, a fellow Catholic, agreed to join him. And before leaving for boot camp, his aunt gave him the precious rosary for his journey.

While fighting in Cambodia, three other soldiers joined Nguyen and Noi on their escape. In 1981, all five deserted and began the dangerous journey on foot through Cambodia. “There was a risk of land mines and four other fighting forces all fighting each other,” Nguyen says.

While on the run, the two Catholics – Nguyen and Noi – found a quiet spot to pray each night. “We prayed the rosary together and asked for Mary’s intercession to make the trip,” he says.

Together, all five men made it to a refugee camp on the border of Cambodia, just one kilometer from Thailand. At the camp, run by the International Red Cross, Nguyen met his future wife, Hahn Long. And while there, he continued to pray the rosary.

“The cross was broken while I was in the refugee camp,” he recalls. “I replaced it with one I made from a flattened aluminum spoon.”

The men lived in tents for two years with 2,000 other refugees until shelling between the Vietnamese and the Khmer Rouge of Cambodia made it too dangerous to stay. They were all evacuated to Thailand for safety. Another miracle, Nguyen now says, amazed he did not perish during the shelling. Later, at a Philippines processing station, he was sponsored by Catholic Charities of Hartford.

Nguyen arrived in Hartford in 1983 as a “political refugee,” while Long initially settled in New York City with family. “She took the RCIA course,” he says, “and became Catholic before we married on November 29, 1987 at St. Lawrence O’Toole Church in Hartford.”

Even so, the transition wasn’t easy. “Even when I got here, there was fear,” Nguyen admits. “I could not speak the language. I thought about going back but my faithfulness in going to church and praying lifted me up and helped me to get through the tough times.”

Nguyen eventually became a U.S. citizen. Today he has three grown children and a career as an electronics engineer. Over the years he has stayed very close to his Catholic faith, teaching high school confirmation classes, singing in the choir, and attending two Masses every Sunday at St. Andrew Dũng-Lạc Parish.

He’s grateful for his fellow parishioners, who have carried on the Vietnamese culture by teaching their native language to parish youths. He also joins them in sharing their Catholic faith by teaching children to trust in Jesus and Mary.

And Nguyen has never lost that trust. He keeps his aunt’s rosary close by. “The beads have worn out so much that I dare not use it,” he says, “but I have it as a reminder of my past and the graces I’ve received through Mother’s intercession.”